Mortal Engines, or Why Steampunk Went Off the Rails in Cinema

When a big-budget production dares to imagine steam-powered cities locked in a relentless mechanical hunt, the result can hardly leave anyone unmoved. Mortal Engines is one of those excessive, fascinating, and deeply uneven works that embody both the boldness of steampunk on the big screen… and its limits when faced with the modern Hollywood machine. Yet this ambitious blockbuster, as mesmerizing as it is peculiar, turned into a commercial disaster. A look back at a shipwreck foretold—one that may well mark the end of an era for large-scale fantasy cinema.

Backed by the looming presence of Peter Jackson and adapted from Philip Reeve’s novels, Mortal Engines set out to make steampunk a genre capable of uniting a broad international audience. Released in U.S. theaters on December 14, 2018, the film struggled to find its footing, held back by mixed reviews and an overcrowded blockbuster marketplace. The result: it quickly established itself as one of the biggest box-office bombs in cinema history.

Image credit: Universal Pictures

A steampunk universe brought to the screen under Peter Jackson’s influence

The story of Mortal Engines unfolds in a post-apocalyptic future. A nuclear cataclysm known as the Sixty Minute War has devastated the planet. Since then, natural disasters—earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis—have become commonplace. To survive, cities have taken to the move, mounted on colossal tracks. Resources are scarce, and steam has once again become the primary source of energy. In this new world order, the largest cities literally hunt down and consume the smaller ones to expand their power.

Within this nightmarish setting, two destinies collide. Tom Natsworthy, a naive young apprentice historian, is violently torn from his ordinary life. Opposite him stands Hester Shaw, a heroine shaped by a broken childhood and marked by a scar that defies Hollywood conventions, driven by a deeply personal quest for revenge. Together, they become pawns in a conflict far greater than themselves—one capable of reshaping the balance of the world.

Peter Jackson carried the dream of adapting Philip Reeve’s novel series for nearly a decade. The three-time Oscar winner was captivated by the idea of mobile cities devouring others for their resources—a concept never before seen on screen and rich with spectacular visual potential. Initially intending to direct the film himself, Jackson ultimately found himself consumed by The Hobbit trilogy. He entrusted the project to Christian Rivers, a longtime collaborator. The choice made sense: Rivers had grown professionally under Jackson’s wing, from storyboards on Braindead to visual effects on King Kong, work that earned him both an Oscar and a BAFTA. Co-produced by Media Rights Capital, Universal Pictures, and WingNut Films, the movie saw Jackson co-writing the screenplay with Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, while Rivers took on the heavy burden of delivering his first feature film as a lead director.

A critical and commercial failure

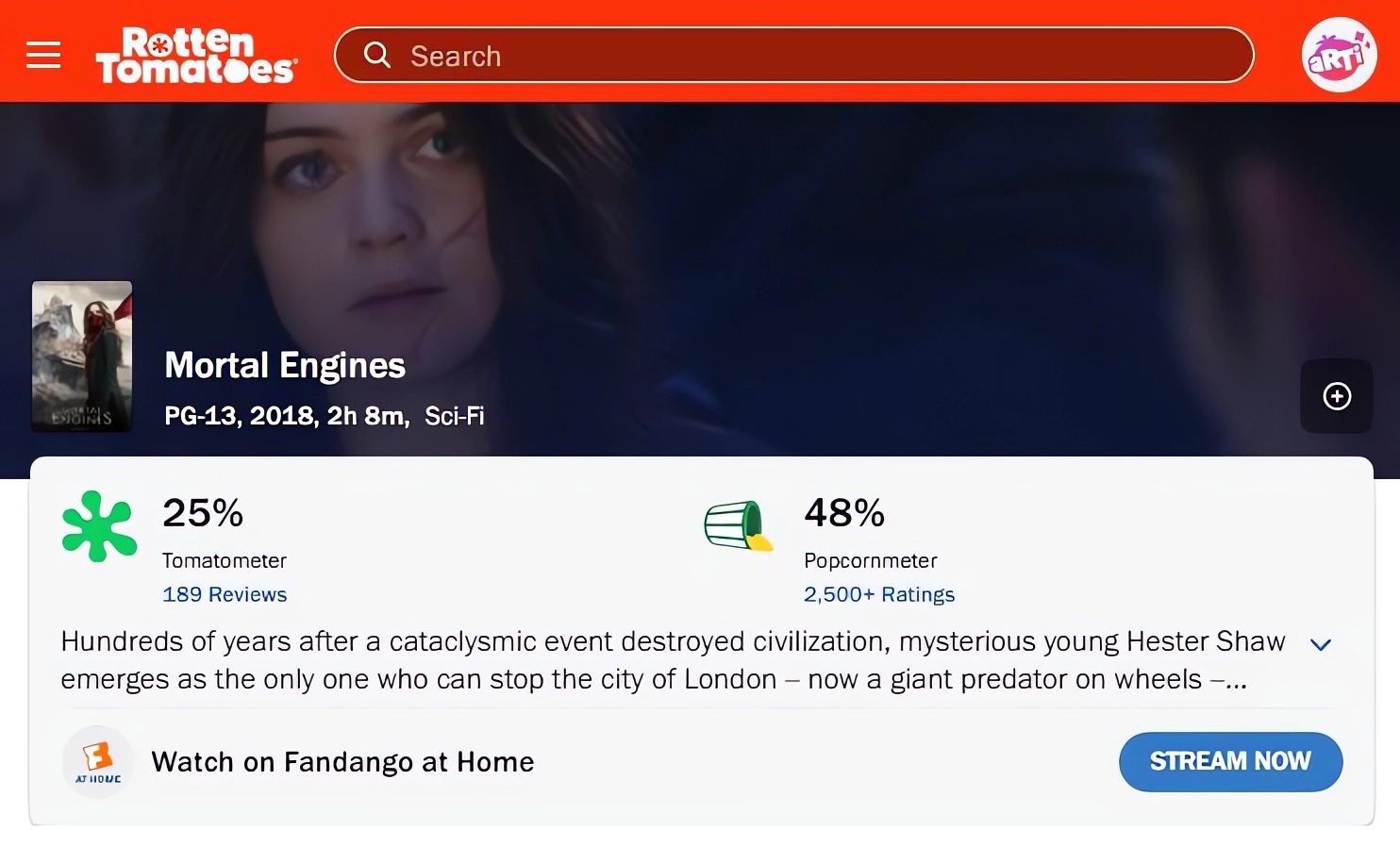

Despite its towering ambitions, Mortal Engines crashed headlong into the harsh reality of the box office. While Philip Reeve himself praised the film as a spectacular work with genuine emotional weight, critical reception was far less forgiving. On Rotten Tomatoes, only 25% of critics responded positively, citing a storyline too muddled to support its visual aspirations. Metacritic lists a score of 44/100, reflecting a decidedly mixed response.

The financial verdict was even harsher. With worldwide box-office revenues of just $83.7 million against an estimated production budget of $110 million—plus massive marketing costs—Mortal Engines reportedly generated losses of around $174.8 million, according to Deadline Hollywood. A financial abyss.

Why failure was almost inevitable

Several factors combined to turn this ambitious production into an industrial-scale wreck. First, the film was released in the middle of the crowded year-end window, squeezed between Ralph Breaks the Internet, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Mary Poppins Returns, Aquaman, and Bumblebee. Peter Jackson’s name, relegated to a producer credit, was not enough to make it a must-see event.

Second, the world of Mortal Engines was largely unfamiliar to mainstream audiences: Philip Reeve’s literary saga lacked the mass recognition of Harry Potter or the mythic status of The Lord of the Rings, making instant buy-in far more difficult.

On top of that came the film’s narrative complexity. Its central idea—roving cities consuming one another—however original, required substantial exposition. This dense world-building complicated the film’s marketing, which struggled to clearly convey its stakes in a few images or catchy taglines. The problem was compounded by the absence of truly bankable stars capable of drawing audiences beyond the concept itself. Peter Jackson would later acknowledge just how risky it has become to launch an original franchise in today’s Hollywood landscape.

The swan song of unconventional blockbusters?

The tragic fate of Mortal Engines fits into a broader—and troubling—trend. The golden age of fantasy cinema, embodied by Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings, appears to be well and truly over. Since 2014 and the final installment of The Hobbit, superhero films have taken near-total control of the big-budget market.

Attempts at revival have frequently failed: The Golden Compass in 2007, young adult adaptations like The Maze Runner or Divergent, and more recently the Fantastic Beasts series, which has struggled to recapture its original magic. Even Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, an ambitious space opera based on a European comic, collapsed so violently that it led to the shutdown of its production company within a year.

These repeated setbacks raise a fundamental question: is Hollywood ready to abandon large-scale original productions altogether? If further financial disasters of this magnitude occur, such films may simply vanish from the cinematic landscape. In that scenario, Mortal Engines would stand as a relic of a bygone era—a nostalgic testament to a time when Hollywood still dared to take creative risks with serious money.

A steampunk monument that will outlive its box-office failure

Yet amid the smoking ruins of Mortal Engines’ commercial collapse, something continues to turn. An ambition that refuses to die, gears that keep captivating despite a hostile market. Admittedly, the film has narrative flaws: overt borrowings from Mad Max or Star Wars, and occasionally predictable archetypes. But focusing solely on these misses the point. Mortal Engines is driven above all by a level of visual richness rarely seen in modern cinema. The high-speed mechanical cities, monumental steam-powered architecture, grinding machines, and meticulous world-building create a coherent, instantly recognizable universe—deeply steampunk at its core. Few recent blockbusters can claim such a strong identity.

In hindsight, the film may yet find a second life—as a steampunk cult classic, flawed but sincere, rediscovered by audiences drawn to its imagination and audacity. A work that, like the cities it portrays, moved too fast and too forcefully for a world that had grown cautious.

And perhaps that is Mortal Engines’ true tragedy: dreaming too big, too soon, in an industry obsessed with safety and repetition. Not a film undone by its flaws, but by its refusal to conform. A steam-driven creation consumed by a Hollywood machine far more powerful than itself.